Interview with Marilène Oliver

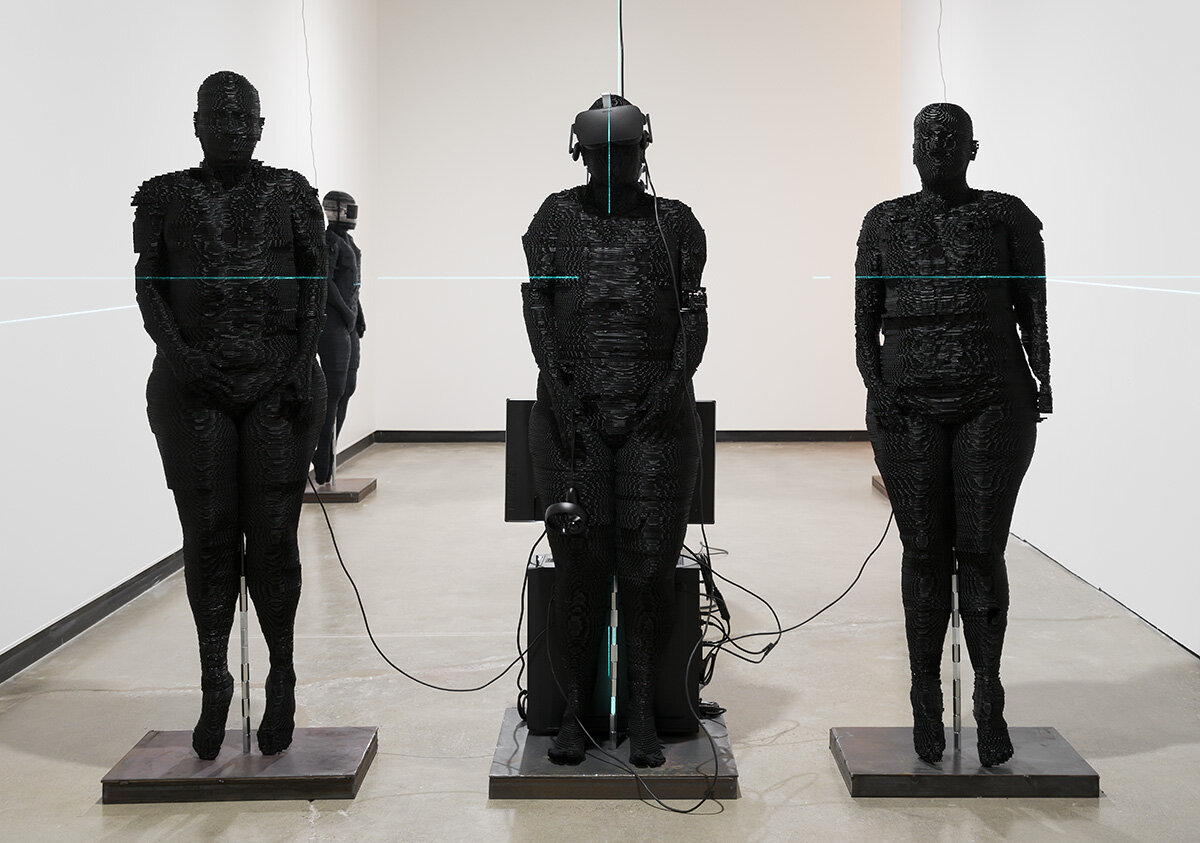

Marilène Oliver works at a crossroads somewhere between new digital technologies, traditional print and sculpture, her finished objects bridging the virtual and the real worlds. She works with the body translated into data form in order to understand how it has become 'unfleshed', in the hope of understanding who or what it has become. Oliver uses various scanning technologies such as MRI, CT, and PET to reclaim the interior of the body and create works that allow us to materially contemplate our increasingly digitized selves.

You arrived at the UofA in 2016, as an assistant professor in printmaking in the Department of Art and Design. Can I ask how your work has changed since coming here? What do you find most exciting about being at the UofA?

Coming to the U of A has allowed my work to expand in many ways thanks to the openness of fellow researchers and artists here, the support when applying for research funding, and, of course, access to world class facilities.

Firstly, I've been able to collaborate with researchers in radiology and computer science. What’s been so great about that is not only that I've been able to find great colleagues and have conversations with them to gain invaluable insights into the way they work and structure their research on a practical level, but it has allowed me to acquire some new MRI scan data which is what I use to make my artworks. Being able to work interdisciplinarily and research-creationally across the arts and sciences has been invaluable.

What are you working on now?

Last year, based on this initial research, I was awarded a coveted KIAS Cluster Grant to support a project called Know Thyself as a Virtual Reality with researchers from rehabilitation medicine, radiology diagnostic imaging, nursing, digital humanities, philosophy, music, law, public health and many more. Having input and insights from such a diverse team really allows the project to be fully rounded and pushes us all to ask questions and seek answers we could never have imagined outside of this project.

I work interdisciplinarily. Though I was hired into printmaking, I also teach and make work in new media and sculpture. Recently, I've been able to realize some very ambitious print and sculpture projects, one which was to create a life-sized figure from copper [insert image?]. I was also very fortunate to get funding in order to buy a laser cutter for our print studio, and I've made many sculptures using that laser cutter [insert image?]. What's so exciting for me about this is that until coming to the U of A I was always working with fabricators in order to make the work for me, and I wasn't really able to intervene in the process. Now I'm empowered to be the one controlling the machine and understanding how it works- to stop it, to experiment, to build a partnership with a digitally mechanized machine – which [science and technology scholar] N. Katherine Hayles might understand as a posthuman action / state of exploration!

This all sounds incredibly rewarding. Any particular shout-outs?

Since arriving at the UofA, I've received some great mentorship with regards to research. This has come from many different people within my own department, but also in other departments across the university. In particular, Geoffrey Rockwell [director of the Kule Institute for Advanced Study] has been incredibly encouraging, as has Astrid Ensslin [former director of Digital Synergies Signature Area] and Heather Young Leslie from the Grant Assist Program. Their faith and encouragement made me persevere through several attempts to get funding for my research, which last year was finally successful.

Being awarded a SSHRC has allowed me to start working on some new virtual reality projects. They're based on the scan data that I acquired before, but now layered with other kinds of data - social media data, Mac computer usage data, my shopping history data. So for example, I am making cross sections of bodies where my Mac terminal data goes inside the bones or my Google data goes inside the muscles, and my social media data goes inside the fat and then running through that there's an arterial system with passwords and logins going back and forth. You can also pick up different organs as they are generating/processing/storing data. This is only one of a set of works I am developing that reflect on what it means to be datafied, different theories about datafication and, and the need to take care of our data, and to understand our data, about data privacy and the need to be aware about how our data can be abused.

These projects are all linked to the feature project here on the SPAR2C website, Dyscorpia: Future intersections of the Body and Technology. Dyscorpia is a project that has really evolved. It started off as an interdisciplinary project working across departments computer science, music, cultural studies and contemporary dance, bringing researchers together to create artworks and mount an exhibition at Enterprise Square. This was an incredible experience that culminated in, I think, a great exhibition which I'm very proud of, and that included a lot of student work as well as a number of invited guests and local artists. The catalogue is available here. I think Dyscorpia really provoked a lot of important discussion and reflection on how technology is changing and controlling our lives and our relationships with each other and the environments we live in/on.

Last year we were just about to hold a catalogue launch event when the COVID restrictions were first announced. Instead, we made an online exhibition with an open call, and it turned into quite a massive exhibition with about 60 artists! Given its success, we may mount yet another iteration this year — so it's really a project that keeps on going, and it does so largely due to support from colleagues and students.

Could you say a bit about how you understand research-creation and how you mobilize it in your work and in your teaching?

I have always sought to innovate and push the boundaries of what art can be, insistent that artists must play a crucial role in how the world knows and sees itself through and with technology. On one level, then, research-creation in my practice involves finding new ways of seeing, new ways of knowing, and new ways of understanding that demand experimentation, risk taking, and interdisciplinary exchange of knowledge and methodologies.

On another level, I recognize how the research-creation process of actually doing — actually making — drives research and ideas in a very different way to other research methods. For example, with the Deep Connection project for which we needed new MR scan data – the first two sets of scans ‘failed’ because the hand was not scanned completely. These ‘failed datasets’ however allowed for the work to evolve and later include sculptural elements based on the ‘failed’ data that enabled the virtual reality piece to ultimately succeed (the hardware was embedded in the sculptures). I encourage my students to be open to this – to be attentive to when the process of capturing, making, actually informs the subject matter and reveals something about it that you could never have imagined. For me, this is the beauty of research-creation: research insights are driven by practice, and they depend on interdisciplinary (and often collaborative!) engagement. As a result, the final form ends up pulling together insights from many disciplines, and it can reach multiple audiences.